In pockets of the Church, such dissent persisted throughout the 1970s and 1980s—including in many Catholic colleges and seminaries, Smith said—with Paul VI doing everything in his power to avoid open schisms while still affirming the Church’s long-held beliefs.

It wasn’t until the papacy of St. John Paul II and his “Theology of the Body” that the average layperson began to really grasp the beauty of Humanae Vitae, Smith said.

“One of the great gifts to the Church was John Paul II, who wrote some of the great defenses of the Church’s teaching on sexuality. The first was his book in 1959 called ‘Love and Responsibility,’” Smith said. The pope's philosophical treatment of the nature of romantic love “is one of the most brilliant works on human sexuality in the history of mankind,” Smith added.

With the help of the pope’s insights and the ability of some orthodox priests professors to puncture walls of dissent, the teachings of Humanae Vitae slowly began to gain traction and appreciation.

“It’s gotten a whole lot better in the last 25 years,” Smith said. “And Sacred Heart is one of those ‘whole lot betters.’ Almost every seminary is a whole lot better. There are a lot of Catholic colleges that have gotten a whole lot better.

“I’m confident because I believe in God, because I believe in the Holy Spirit, that the truth will win out,” Smith added. “I see the young priests we graduate from this seminary and other seminaries, and the revival in religious life of those who are completely faithful to the Church’s teaching, and the laity who are on the march, and I am very confident things will get a whole lot better.”

Sociologist: Parishes key to teaching Humanae Vitae

Michael McCallion, a sociologist and professor of theology at Sacred Heart who studies Catholic behavior from the perspective of societal norms, followed Smith in analyzing the barriers to full acceptance of Humanae Vitae among the Church’s faithful.

McCallion argued that apart from the document’s naturally challenging prescriptions for human life and love, an increasing tendency toward individualism has meant fewer Catholics have the cultural support necessary to live Humanae Vitae.

“It is more unlikely that the teachings of Humanae Vitae will ever be transmitted to people on the move, not because they have not heard of it, but because there are no fellow Catholics to whom they are connected who practice the teachings,” said McCallion, who holds the Fr. William Cunningham Chair in Catholic Social Analysis at Sacred Heart.

In other words, because fewer people in the modern world tend to live in the same place for very long, it’s difficult for Catholics to develop a community of like-minded individuals who can support one another in those teachings, McCallion said.

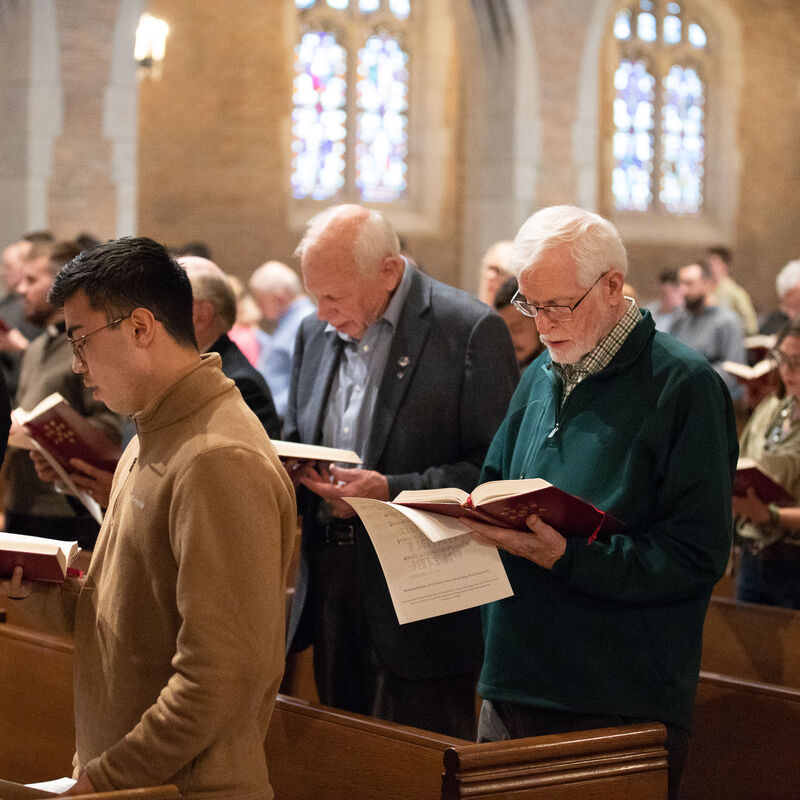

The solution, he argued, is a stronger Catholic version of “a 21st century village”—the parish.

“Sociologists would predict that if a group of Catholics can build up a parish and maintain it over time by staying put physically, members are more likely to follow that tradition, even Humanae Vitae,” McCallion said. “The solution is not necessarily more education and classes—even though that helps. Sociologically, the more important thing is the practice of being in community.”

Also speaking at the conference were Sacred Heart assistant philosophy professor Elizabeth Salas; theology professors Robert Fastiggi and Fr. Peter Ryan, SJ; and Sacred Heart lay graduates Nicole Joyce and Joyce Yurco.

Yurco, a teacher at Spiritus Sanctus Academy in Plymouth, offered conference-goers a reflection on the lay perspective of Humanae Vitae as a document fully rooted in the love of Christ.

“Many of us are called to become a reciprocal gift in marriage. Christ elevated marriage to a sacrament, a means of sanctifying grace. Our reciprocal self-gift in marriage not only creates new members of the kingdom, it is preparing us for eternal life in God,” Yurco said.

“Through his passion, death and resurrection, Christ demonstrates for us and obtains the grace for us to freely and fully offer ourselves in love. On the cross, Jesus is the perfect example of self-donation,” Yurco said. “He demonstrates for us the paradox that by emptying ourselves, through becoming a gift freely given, we become like God.”